In the last few years, the Math department at Rutgers has changed the way it teaches Calculus. This is especially true in the Calculus sequence for the Mathematical and Physical Sciences, Math 151-152.

This is the first of two studies undertaken by the Mathematics Department, as an attempt to determine the relative effect of the new formats. We restrict it to a comparison of the different formats in which we teach Math 151-152. A second report will compare these formats to the old lecture/recitation style we had traditionally used, using data from the Calculus sequence Math 135-136.

Since 1996, we have taught Math 151-152 in 3 comparable formats: the standard 4-credit sections (taken by most students), the 5-credit sections with attached "Practicum" (numbered Math 157-158) and the 6-credit "Excel" sections (which are actually Math 153-154).

To measure the effectiveness of these different formats, we used the common final exam scores for each semester. This test was taken during finals week by almost all students in these courses; the small percentage who needed a make-up test were excluded from our data. In both semesters, the final exam was scored on a scale of 0-200 points.

Here is a brief description of what we found.

We will quantify these conculsions below.

In Spring 1998 the final exam was taken by 540 students and had an average

score of 131 points; only 95 received an 'F' on this exam. A large part of

the reason for the different student profile in Calculus II is that many of

the weaker students in Calculus I were filtered out; the average final exam

score in Math 151 among continuing students was 128, not 116.

We found clear differences in performance between students' scores on

the Math 152 final exam in Spring 1998 (see Table 1).

The differences between the means of these groups is significant at the

usual 95% confidence level, because the Standard Errors (the standard

deviations of the means) in this table are much smaller than the

differences between the observed means.

In both semesters, there is an obvious point to be made: this analysis of

average scores is suspect because it does not take precalculus skills or

aptitude into consideration. This information was available to us in the

form of placement information.

In 1990, Rutgers initiated a 6-credit pilot program called EXCEL for

first-year calculus students. Based on a program at Berkeley, it replaces

the one recitation with three full periods per week devoted to workshops.

The workshops involve collaborative learning in small groups of 3-4 students.

In addition, students are now being asked to write up expository solutions,

explaining in complete sentences how they arrive at their answer.

EXCEL was an immediate success. Not only did we notice an increase in

grade point averages over several years, but we also observed fewer losses

in the number of technical majors. In addition, other departments have

supported EXCEL because they have found that EXCEL students were better

able to engage in collaborative learning projects. Since 1990, EXCEL has

become a standard course offering, and given the designation Math 153-154.

Encouraged by the success of the EXCEL program, the Math department changed

the way it teaches Calculus, starting in Fall 1995. In order to keep the

4-credit course load, each section of Math 151-152 meets 3 times per

week, with two 80-minute periods being devoted to traditional lectures.

In the third period, increased from 55 to 80 minutes, the students meet

in a recitation/workshop format. These classes are led by a teaching

assistant (TA) and a carefully selected undergraduate, called a Peer Mentor.

Typically, the first 20 minutes are spent going over the routine homework

problems. In the remaining hour, the students break up into small workshop

groups (of 3-4 people) and attempt more challenging problems, which are

distributed as a handout. One of these workshop problems is assigned to be

written up in the next week, and graded for both mathematics and exposition.

Starting in Fall 1996, a 5-credit version of Math 151-152 was created.

Again, two 80-minute periods are devoted to traditional lectures.

In addition, the students meet twice a week in 55-minute classes. One

class is a traditional recitation, in which a teaching assistant (TA)

goes over the routine homework. The other 55-minute class is held in the

workshop format described above, and run by the Lecturer and a Peer Mentor.

We will refer to this as the "Practicum" format, since one 55-minute class

each is afflicted with a separate course number (Math 157-158) and the

name Practicum by the University Registrar.

In order to take Calculus I at Rutgers-New Brunswick, all students must

either pass the New Brunswick Precalculus placement exam (the NBPRE) or

else have passed a precalculus course. The NBPRE is scored from 0 to 40;

a score of 19 or higher qualifies them to take calculus. We had the NBPRE

scores for all first-year students, but not for all upper-class students.

The average NBPRE score was 27.0 for the first-year students in our sample.

About 1% of all first-year students had lower NBPRE scores, but were

allowed into Math 151 if they had taken Precalculus over the Summer.

In addition, our database contained admissions information.

We had both the Math SAT (MSAT) and Verbal SAT (VSAT) scores

for all first-year students in our database, scored from 200-800.

We also had their High School Rank (HSR), measured as a percentage from

0-100, their gender (male/female) and school of admission.

The average MSAT score in our sample was 650; almost all students in

Math 151 (excluding EXCEL) had an MSAT of over 580. To no one's surprise,

we determined that the VSAT score was not a significant predictor of the

final exam scores. The average high school rank was HSR=81.4%, with the

first and third quartiles being 72.8% and 93%, respectively.

For Fall Semester, there was little statistical difference between the

placement scores of the first-year students taking the standard sections

and the practicum sections. This is illustrated in Table 2.

However, the profiles for the students in EXCEL were different.

This was no accident: selection into EXCEL is done by each College (primarily

Douglass College or the Engineering College) on the basis of these numbers.

An analysis of these scores yields the following table.

Comparing the Standard Error with the means, we see that only the

mean for the Practicum sections is significantly higher. However, this

does not mean that there are no differences -- because the mean does not

take a student's prior skill level into consideration.

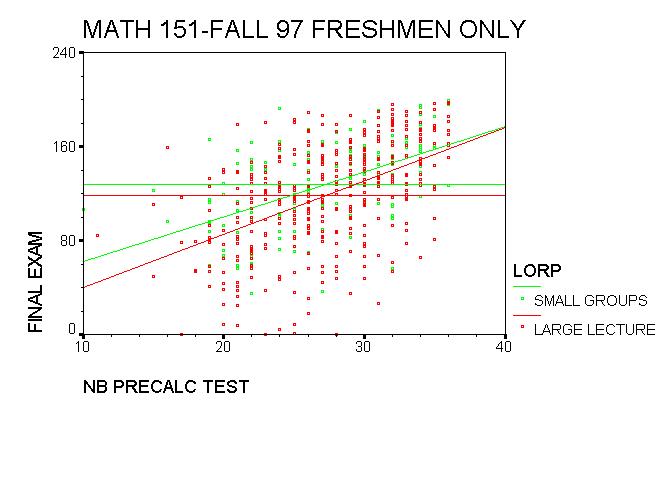

Using only the NBPRE placement scores for first-year students,

a regression for the final exam score F151 yielded the best linear fits:

After adjusting for the placement scores, we see that weak students did much

better (16-18 points better) in the Practicum and Excel sections, with the

students in EXCEL doing slightly better. The same is true for students with

average and high placement scores.

Here is a scatter plot of NBPRE placement scores versus 151 final exam scores.

This model is one more confirmation of the success we have seen in EXCEL,

and which has been documented before. Because the number of students in

EXCEL was so small, and had a different profile, we excluded EXCEL (Math 153)

from the rest of the study. Since 45 of the 46 students in EXCEL were

first-year students, the main study which excluded Math 153 contained

560 first-year students. Out of these, we had full placement information

for 545 students.

One such study is

"Prediction of Grades in College Mathematics Courses as a

Component of the Placement Validity of SAT-Mathematics Scores," by

B. Bridgeman and C. Walker of ETS (published by the College Board in 1990).

In their study, they found that local placement tests like the NBPRE

have a good correlation (about .5) with Calculus grades. In contrast,

the MSAT, which is only a general measure of mathematical aptitude,

only had a correlation of about .35 with Calculus grades.

The NBPRE and MSAT scores are not independent variables;

the correlation between NBPRE and MSAT was .49 for the first-year students

in our study. In addition, the MSAT is a factor in admission to Rutgers,

while the NBPRE scores are used in placement into Calculus and Precalculus

classes at Rutgers-New Brunswick.

We performed a Factor Analysis on the variables F151, NBPRE, MSAT and HSR

in order to determine if there was a better indicator variable.

It turned out that there were two significant factors, with eigenvalues

2.1 and 1.0. The most significant factor was:

(F151, NBPRE, MSAT, HSR) = (.78, .28, .82, .87).

The secondary factor was essentially the HSR. To test the effect of this

factor, we defined two new predictor variables,

NEWP = (0.87)NBPRE + (0.82)MSAT + (.28)HSR,

This had correlation coefficients of .56 and .55 with the final exam scores

F151 of the first-year students, compared with the correlation of .52 for

the NBPRE alone. We confirmed by visual inspection of the scatter plots of

the data that there was not a real difference between working with NBPRE of

the factors NEWP or REGR.

Apparently this was because 90% of the scatter was absorbed by the NBPRE.

FINAL = (9.0)LORP + (3.37)NBPRE + (.45)HSR + (0.169)MSAT - 121.2

In summary, given identical placement data, a student in the practicum

sections could expect to score about 9 points higher on the final exam.

Clearly the students who had not taken Calculus I in the previous semester

("none") did not fare as well. Students who had taken Math 135 also had

lower scores, but this was not statistically significant. Since it seemed

clear from the data (and experience) that the performance in the Calculus I

course was significant, we excluded these students from further study.

Next, we analyzed the data for the students in Math 154 (EXCEL).

Of these, 24 students had taken Math 153 (EXCEL) in the fall, and 21

had taken Math 151 (17 took the 4-credit, and four students took the

5-credit version of Math 151). One student had taken Math 152 in the Fall,

and did very poorly on the final, so we excluded him as an outlier. Faced

with these small numbers, we had to content ourselves with general trends.

For these 45 students, the average score was 145.9, significantly higher

than the scores of students who had never been in EXCEL. This included

6 students who flunked the final exam (scored below 95 points); all of them

had also flunked the final exam the previous semester. The 21 who came from

Math 151 into EXCEL averaged 150 on the final, with no significant correlation

to their performance on the 151 final exam. The 24 who took EXCEL both

semesters had an average final score of 146.5, and there was a significant

correlation with the Math 153 final score (F153):

When we restricted to first-year students with full placement data,

who took Math 151 in the Fall, and excluded the 45 students in

EXCEL (Math 154), we had 316 students in the study.

In Spring 1998 we had final exam data for 540 students. However,

since we wanted to analyze the effect of the previous semester's final,

and we wanted to exclude EXCEL, we had only 388 students in our study.

This included 348 first-year students, for which we had both the Math 151

final score and all placement information. There were 91 other first-year

students with incomplete data which we ignored.

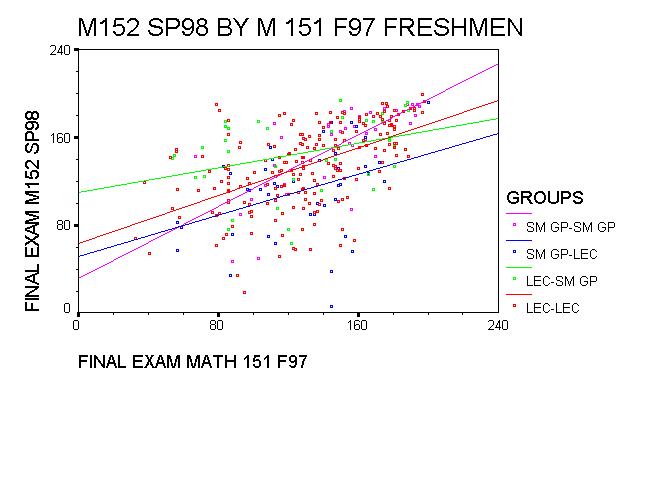

Here is a scatter plot of 151 final exam scores vesus 152 final exam scores.

We considered the LL group (students in the standard 4-credit version both

semesters) as our control group. The correlation between the Fall and

Spring final exams scores was reasonable (.54), and there was a concomitant

correlation with the MSAT and NBPRE scores (the correlations were between

.4 and .44).

Clearly the worst scores are in the PL group, the group of 45 students who

went from the Practicum to the Standard sections. In searching for features

of this group that might explain this, we observed that their final exam

scores were almost independent of the MSAT and NBPRE scores (the correlations

were .01 and .17).

The LP group, consisting of 50 students who switched from the Standard

sections to the Practicum sections, was equally interesting. Their

scores were significantly higher than those in the control group.

Here the curious feature was that the Math 151 final score was almost

independent of the predictors MSAT and NBPRE (the correlations here were

.17 and -.07, respectively).

The best performers were in the PP group (in the Practicum both semesters).

For this group there was a very strong correlation (.77) between the

Math 151 and 152 final exam scores.

Multiple Regression for Math 152 FINAL

Average Final Scores

In Fall 1997, the final exam was taken by 700 students and had a mean score

(average) of 116 points; 199 students received an 'F' on this exam. There was

no significant difference between average scores of the 4-credit sections

and the 6-credit (EXCEL) sections (114 versus 116), but the average score

for the 5-credit Practicum sections was 125, which is significantly higher.

Class # of Average(mean) QUARTILES Standard

Format Exams and Std. Error First Median Third Deviation

------ ---- ------------- ----- ------ ----- -------

All sections 540 130.6 (1.7) 107 136 165 40

Standard 378 127.5 (1.9) 102 130 156 37

Practicum 120 134.8 (3.3) 112 139 167 36

Excel (154) 42 146.5 (5.0) 130 152 167 33

Table 1. Final Exams from Math 152 in Spring 1998

The Formats used in the courses

Until recently, all Calculus at Rutgers was taught in a traditional

4-credit format, consisting of two 80-minute lectures and one 55-minute

recitation each week. Most sections of Calculus 135-136 are still taught

that way, but this is no longer the case with Math 151-152.

Placement Information

We had a large database of placement scores for first-year students,

which we were able to combine with the final exam scores for the first

and second semesters of Calculus.

Class Format # FY NBPRE MSAT HSR

------ ------- ----- ---- ----

All sections 605 27.04 650 81.4

Standard 408 27.43 653 82.1

Practicum 152 27.12 664 81.6

Excel (153) 45 23.30 570 74.3

Table 2. Placement statistics for

first-year students in Fall 1997

The First Semester Results

In Fall 1997 we had final exam data for 689 students, including

605 first-year students. The mean for all students was 116.4 points, and

the mean for first-year students was 120.8 points, not a great difference.

Because we had available the admissions data for first-year students,

and because this information was correlated with final exam scores,

we decided to report our statistical analysis for first-year students.

The analysis of all students was also done, but the results are

qualitatively similar and less complete.

Class # Exams Mean Std.Error Standard

Format ALL(FY) ALL(FY) ALL(FY) Deviation

------ ------- ------------ --------- -------

All sections 689(605) 116.4(120.8) 1.7(1.8) 44(43)

Standard 478(408) 113.6(118.7) 2.0(2.2) 45(44)

Practicum 165(152) 124.8(127.8) 3.1(3.0) 39(37)

Excel (153) 46 (45) 115.8(116.1) 6.0(6.1) 41(41)

Table 3. Final Exams from Math 151 in Fall 1997

FORMAT Least squares equation NBPRE=23 NBPRE=27 NBPRE=31

--------- ------------------------- -------- -------- --------

Standard: F151 = (4.87)NBPRE - 15.3 96.7 116.2 135.7

Practicum: F151 = (3.87)NBPRE + 23.2 112.2 127.7 143.2

Excel: F151 = (4.16)NBPRE + 18.3 114.0 130.6 147.3

Figure 1: PRECAL placement scores versus 151 Final Exam scores

Finding the Best Predictor

In our study, both the New Brunswick Placement Exam (NBPRE) and the

Math SAT scores (MSAT) were highly correlated with the final exam scores;

their correlation coefficients were .51 and .41, respectively. This suggests

that we use a combination of the NBPRE and MSAT scores as a predictor of the

final exam scores. This is supported by research studies which show that

both the NBPRE and MSAT scores are indicators of performance in Calculus.

REGR = (3.37)NBPRE + (1.69)MSAT + (.45)HSR.

Lecture or Practicum?

We also ran a more sophisticated stepwise linear regression, using the

t-test to decide which variables are significant. This showed that the

High School Rank (HSR) was just as important as MSAT scores in predicting

final exam scores. To determine the effect of the format, we introduced

the indicator variable LORP, defined to be zero for Standard

sections and one for Practicum sections. The best linear fit was:

The Second Semester Results

In Spring 1998 we had 543 students take the Math 152-154 common final exam.

In addition to placement information, it was important to know which

Calculus course they had taken in the previous semester. There were

115 students did not take Calculus I in the fall, 22 who had taken Math 135,

the other Calculus I class offered by Rutgers, leaving only 406 students

who had taken Math 151-3 in the Fall. Their scores on the final exam (F152)

are summarized in the following table.

Two-term # F152 std. std. Two-term # F152 std. std.

Sequence Exams mean error dev. Sequence Exams mean error dev.

-------- ----- ---- ----- --- -------- ----- ----- ----- ---

any-152: 543 131 1.7 39 151-154: 21 145.4 6.8 31

none-152: 115 125 3.5 38 153-154: 24 146.5 6.7 33

135-152: 22 129.6 7.7 36 153-152: 26 141.5 7.1 36

151-152: 406 134 1.9 38

Table 5. Final exams in Spring 1998 by Course Sequence

Least squares equation F153 score: 100; 116; 130; 150

EXCEL 154 FINAL = (0.58)F153 + 79.2 137.2 146.5 154.6 166.2

By visual inspection of the scatter plot, it appeared that this equation

gave a good fit for the best students, and was not skewed by the

six poor students in the sample. The slope of this line was similar

to that of the least squares lines for Math 151-152 below, reflecting the

reality that the final exam for Calculus I is a good predictor of the

final exam score for Calculus II.

151/152 # 152 Std. Std. F151

Formats Exams Mean Err. Dev. Mean NBPRE

------ ----- ----- ---- ---- ---- -----

All sections 388 132.4 1.7 37.5 130.3 28.2

LL (control) 251 130.3 2.5 36.8 129.0 28.3

PL 45 111.4 6.2 41.9 126.7 26.2

LP 50 144.5 5.2 36.8 128.4 29.0

PP 42 152.9 5.8 37.6 144.6 28.5

Table 6. Final Exams in Spring 1998

All students, by format in both semesters

Figure 2: Final Exam Scores: Calc I versus Calc II

versus Math 151 Final (F151), NBPRE, LORP and PRELORP for first-year students.

FINAL = (.543)(F151) + 63.4

= (.432)(F151) + (2.04)NBPRE + (15.2)LORP + C'

= (.450)(F151) + (1.85)NBPRE + (18.9)LORP - (11.7)PRELORP + 22.3

weibel @

math.rutgers.edu